Ghosts: Part 3

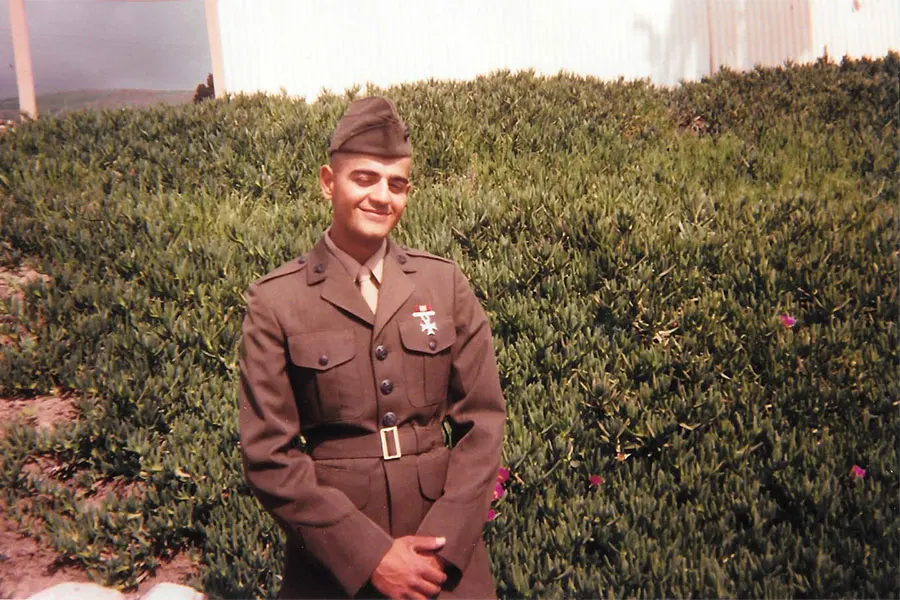

The recollection of a young mans enlistment in the Marine Corps and the memories of M.O.S. school at Aberdeen Proving Ground.

I have a journal that begins right after my boot camp leave, when I flew back to California for Marine Combat Training. This journal is embarrassing to read at its best, cringey and vacuous at its worst. Even though flipping through its pages leaves me slightly nauseous, I’m thankful I have the opportunity to revisit them. When they’re actually reporting something instead of blathering on in vain attempts at humor and sophistication, they create small snap-shots of a time and place and where I was emotionally. The predominant theme that emerges from those words is how much I hate the life I chose. There are often moments interspersed between my whiny laments where I’m doing my best to look at things in an optimistic light, though they dramatically diminish as the pages progress.

It’s easy to be hard on that kid, to sit here from this vantage point and write that he was being “whiny”. Some of it was simply a boy, eighteen years old, complaining about what he was experiencing. Yet there was more to it, and that young man was, and still is, worthy of my empathy.

As inelegant as this sounds, it sucks growing up poor. I was fortunate to some degree, as the “poor” I experienced was a far better financial situation than many others. What that means is we didn’t go without food. We had a roof over our heads. We were clothed. All of the basic needs for human survival were met. In a better world, one where your parents are not overwhelmed by stress, exhausted by exploitative work, worried day in and day out how ends were going to be met, where they still have the wherewithal to show you love…in that world, even with tight finances, it could be more than enough. You can likely live through some fairly harsh circumstances as a child, and come out the other side well balanced and nurtured when your parents are a rock of stability and love.

Extreme financial stress and worry was the norm and it abetted the other dysfunctions of our household until it felt hot and taut with anxiety. My home felt like a pressure cooker, and inside this pressure cooker there was a daily, every man for himself, gauntlet to be run.

That wasn’t my world. Tenderness was in short supply in my world. I knew my parents loved me, or so they said, but the demonstration of that love was often displaced by anger and violence. Sadly it was an all to familiar situation to find myself being told, “I love you”, after my father had exhausted himself beating me. Extreme financial stress and worry was the norm and it abetted the other dysfunctions of our household until it felt hot and taut with anxiety. My home felt like a pressure cooker, and inside this pressure cooker there was a daily, every man for himself, gauntlet to be run. Each day I awoke feeling worried, and went to bed anxious each evening, surrendering to sleep as the temporary escape hatch it was. At some point I began strategizing how I could stay more than an arms length away from my father. I learned to be quiet around him in an attempt to make myself seem small and still and absent. This was in hope of avoiding becoming the target of his disappointment and anger. Sometimes it worked.

The reality is I didn’t realize we were financially poor as a young boy. I knew money was tight, but I did not realize how bad off we were until I was a teenager. Yeah, I took the taunts as a kid, getting teased about my “plastic shoes”, the cheap six dollar pairs my father insisted on getting us and then became furious when they fell apart two months later. As a young boy I didn’t understand why my dad couldn’t cough up two dollars for me, instead getting angry and belittling me when I asked, not realizing he likely didn’t have it to give. At times I worried over getting found out that my parents shopped at Kmart when it came time to get us boys new clothes. But situations like those were mostly in the background. Prior to being a teenager they didn’t occupy much of my reality. But I damn well knew we were emotionally poor. Whatever it was that was going on, I was cognizant enough to see the effect it had on our home life, and particularly, my father.

By freshman year in high school my life at home began to take a toll. Years of emotional and physical abuse had chipped away at my ability to see the next day as promising the possibility of something better. I began to lose hope. In the end, and I’m purposely glossing over the ugly details, I was diagnosed as clinically depressed and spent a month and a half in a psychiatric ward. This was a nice vacation from all of those stresses and worries. It was a safe, comfortable space where I could decompress. It felt so safe and comfortable I cried when I had to leave.

Once home, my family were at their best behavior for a few weeks until it all settled back into the same well-worn groove of dysfunction. The only difference now was my father abstained from beating me. From this time forward he would periodically remind me what a waste of money my hospital stay had been. I could only hear this as him preferring me dead over spending the money attempting to help me.

I was a smart kid. When I first entered high school I had a full load of accelerated classes. By my third year I was barely keeping afloat. I was removed from all those honors classes, picked off one by one due to failing grades and lack of effort. I was being shuffled along, moved through the system, being kept out of everyone’s hair. Just another kid being schlepped out the door into the arms of the working class. I had tons of potential, but it was going to waste. If anyone recognized something in me, they didn’t reach out. There is the possibility I was incapable of seeing a helping gesture even if one had been made. It’s even possible I pushed help away. All I know for sure is when reflecting back to this time I’m saddened there were no adult mentors in my life.

For a small contingent of the poor, desperate, downtrodden youth of America, this is most likely a well-worn path to lifting oneself out of horrible conditions and creating a new and better life.

I started getting in trouble and on a couple occasions I was arrested for misdemeanor possession and underage alcohol. I was depressed and self-destructive. I felt aimless and lost. I was often angry, rebellious, and antagonistic. I withdrew from people. I aligned myself with a life view that looked at everything from the lowest common denominator. It was all a farce, all bullshit.

What all this boils down to is these situations and circumstances led to that off-the-cuff decision to join the Marine Corps. Having suffered abuse for many years I was looking for a way out. I found it. Then I realized I had jumped from one pressure cooker into another and I was miserable. Anyone could shrug and say, “Hey, you knew what you were getting into”. I thought I knew, but the reality of being in the Marine Corps was unlike anything I was capable of imagining. The military relies on the enlistment of young men and women, preferably when they’re at their peak physical fitness and when they’re most naive about the life decisions they’re making. Plain and simple, I was naive. And I wasn’t alone.

I found a tribe in the Marine Corps. We were a group of young men, all of us boys practically, with similar backgrounds. Our group was comprised of former drug addicts, and alcoholics, and young men on the run from their lives. We were young men from broken homes, making last ditch attempts at the behest of a judge, or a pleading family member, to do something, anything, to change the course of their lives. We all made the same desperate decision: join the Marine Corps as a way out.

For a small contingent of the poor, desperate, downtrodden youth of America, this is most likely a well-worn path to lifting oneself out of horrible conditions and creating a new and better life. This came with a gamble for myself as well, a run of the odds as to whether this great death machine I joined as a bridge to a new life was going to send me off to war to be reconstituted into battle sausage. It was peace time when I joined, but as I would see only a year or so later, peace time was a fragile idea that could give way with the slightest provocation.

I was quickly realizing my mistake. I didn’t want to kill people. I wasn’t a tough guy. I didn’t have dreams of war time accolades. I didn’t want to play solider. I was an introvert. I liked to read, and write bad poetry, and draw and paint. Not the greatest fit for an institution that prided itself on being the first into a conflict zone and the last out.

Marine Combat Training

“I got put on a working platoon which is good ‘cause I only have it for a week. I get the most sleep and liberty compared to the other working duty’s so I guess that is something to be thankful for.

“Anyway, I’ve just been doing bullshit jobs the past few days. Going around cleaning up trash, hauling weapons. Today we emptied an armory shack into a couple of trucks. The weapons weighed like 50 pounds each.

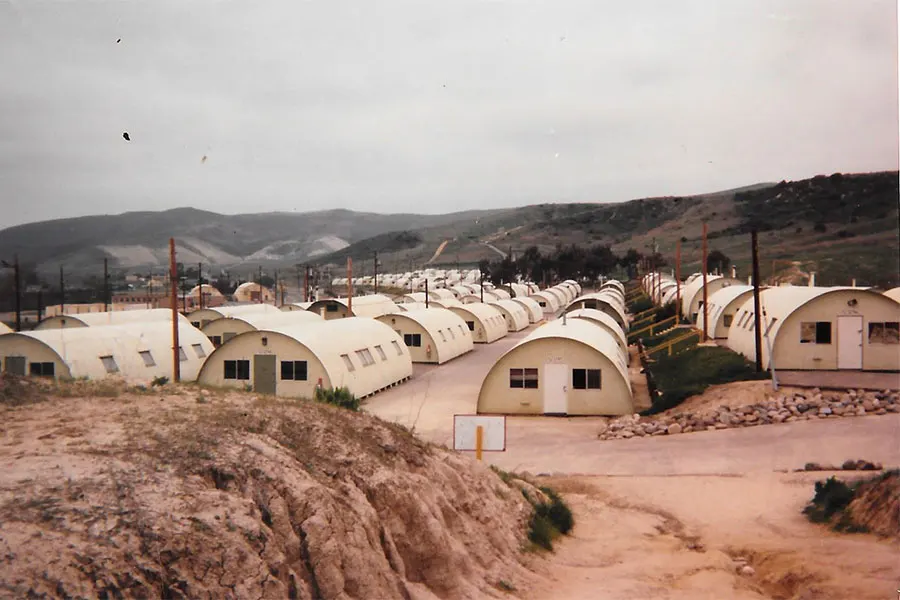

“I’m living in a little shack called a Quonset Hut with my working party platoon. So far it’s been alright. We all get along so I guess that is something to be thankful about. We work from 6:00 or so until 6:00 at night. Then we’re turned to free-time.

“I’ll tell ya – I’m in some beautiful land. We’re in a valley between all these mountains and the weather is great. It was cool, the other day the Gunny took us on a kinda scenic drive through the mountains. I think he just wanted to finish his cigar before we went to drop the trash off, but it paid off for us. We were in the bed of the truck and the mountains were beautiful. I was overwhelmed by them. They made me think of old, wise grandpa’s, or icebergs making their slow travels across the sea.”

– February 11th, 1994

That first week was filled with busy work while I waited to be dropped into the next training cycle. We traveled up and down the mountains everyday, picking up trash from the platoons in the midst of their field training, bringing in hot meals, water, and ammo. My entries are dotted with attempts at optimism, of looking at the way I was feeling as temporary, but it comes across forced and insincere. By the time I landed in my Marine Combat Training platoon (Golf Company Platoon #2) I was already stating I was “tired of the Marine Corps bullshit”.

Marine Combat Training was the month of extra training that non-infantry Marines were required to complete after boot camp. Marine Combat Training was kind of a boot camp light, though there was more time playing solider and wallowing in the mud. We continued to be harassed by our squad leaders and Sargent’s, spent our time humping in the field (long-distance, full gear hikes throughout the mountainous countryside), playing war games, and shooting a variety of weapons.

I don’t have many memories of this month. Most of my journal entries are laments about missing my friends and my girlfriend, about wanting to get the training over with. There are diatribes about some of the people, the realization that I was part of a gigantic death machine capable of unleashing unimaginable levels of pain and suffering. There are a few entries describing hanging out with a Marine I had been in boot camp with. He was from Iran, and we talked about how it was different from America. He once described cowering with his family as air raid sirens went off and bombs began detonating throughout his neighborhood. He told me of how one of these bombs destroyed the home next to his. We played pool and drank beer on a few occasions, sharing stories of growing up. He was a kind and thoughtful person and I enjoyed his company.

But there is little else other than the training, and there isn’t anything remarkable to say about that. The memories are vague, a handful of snapshots, faces I cannot put names to. In the end my friend from Iran went off to Georgia to train to be a cook. I never saw him again.

I was heading off to the east coast to train as a Light Armored Vehicle mechanic. I had no idea what was ahead of me, but I was tired of the relentless training and busywork. I looked forward to applying myself to something new, learning a skill, anything other than war games and incessant cleaning. I had never been to the east coast and I was looking forward to that as well. I said goodbye to a handful of Marines from my platoon, took a last look around the valley, taking in the mountains and the way the clouds hung around their peaks, and then made my way to the airport.

“Effects was alright (the last bit of training we did…I don’t recall why I called it that). The “alright” being stressed to the extremes. We humped out about five miles to the Effects area. Then we dug foxholes all day, just for it to rain and cover us in mud. It sucked ‘cause we didn’t even stand post in them. I guess we just dug them to know what it’s like.

“Anyway, we went out on our patrol at 8:00 and were back the next day at 3:00 am. The we humped back and started the ritual of leaving.

“Well, Alphy (my friend from Iran. His nickname was Alphabet) went to Georgia for his school which kinda sucks ‘cause he was cool. I hope we see each other again. We said goodbyes at the airport and went our separate ways. I had to sit at the L.A.X. from 2 until 11 to wait for my flight. It was kind of boring. And here I am now, sitting in my dorm.

– March 12th, 1994