I completed the Marine Corps on-boarding process. I spent two days standing in lines and filing into rooms with a hundred other military enlistees for the ASVAB and physicals, to stand in sour, feet smelling offices while we spread our ass cheeks and stuck out our tongues. In short order I was squared away to become a heavy equipment operator after boot camp. I had an idea I wanted to be an artist, but needed a fallback, and this fallback was to work in construction, specifically to build roads. Learning to operate heavy equipment would give me the chance at this after I had fulfilled the terms of my enlistment. I have no idea how blistering all day in the sun and inhaling the smoldering, toxic smell of asphalt was something I aspired to do.

I had a number of months to wait until I turned 18 and shipped out. I was told it would be helpful to lose some weight during the interim. This seemed practical and I nodded in agreement. I proceeded to do nothing of the sort. I arrived at Marine Corps Recruiting Depot San Diego that November at 203 pounds – the heaviest I’d ever been. I struggled to complete the three pull-ups required as the minimum physical competency for enlistment, my legs kicking for momentum in hope of driving me upward, my face reddening from exertion and shame as the other recruits stood by. To be honest, I believe the recruiter was being generous as I failed to pull my chin above the bar on the third.

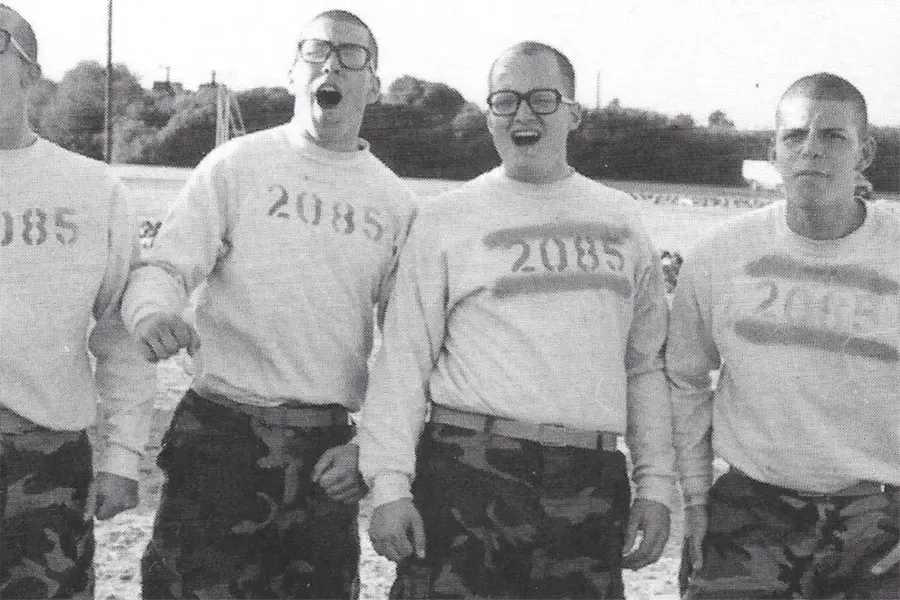

Upon arrival at the Receiving Barracks we were immediately stripped of any defining qualities of our personalities, beginning a process that separated us from our civilian counterparts. Our hair and clothing were removed and we were spat out the other side of the barber shop looking like carbon copies of one another: bald, bewildered drones decked out in camouflage fatigues.

Boot camp is designed to break you down into fundamental pieces and then build you back up into the image of a Marine. This involves a tightly controlled system of indoctrination, as well as physical and mental training. This includes the use of physical duress to get you “motivated” in all the right ways. The days of beating recruits was long over by the time I arrived, though that didn’t stop Marine Corps drill instructors from using extreme exercise and stress positions as punishment. I’d call it torture as it was both excruciating and effective at breaking you down. The drill instructors called this “getting bent” and most often this was conducted at the head of the barracks in the “classroom”.

From the moment you are dropped into your platoon until you graduate, every move, every exercise, every function you are tasked with is in service to your training. For example, something that seems odd though benign in the beginning is the practice of carrying your “knowledge” (a book of information and studies you use throughout boot camp to learn the history of the Corps, how to conduct yourself as a Marine, the Uniform Code of Military Justice, etc.). You are commanded to carry this book in a very particular fashion: elbow tucked into your side, forearm parallel to the ground, your palm supinated and holding tight to your knowledge. Only later, during the second phase of boot camp, do you understand you’ve been training yourself to properly hold the butt of your rifle while marching.

Upon arrival at the Receiving Barracks we were immediately stripped of any defining qualities of our personalities, beginning a process that separated us from our civilian counterparts. Our hair and clothing were removed and we were spat out the other side of the barber shop looking like carbon copies of one another: bald, bewildered drones decked out in camouflage fatigues. They did not allow us to sleep and I lost track of the time, moving through the receiving process as if in a dream. I was processed with my fellow recruits over the course of what I believe was two days. Once processing was complete we were dropped into our platoon – a sorry looking lot of sleep deprived recruits. The intake Sergeant handed us off to our platoon Staff Sergeant, Staff Sergeant Brown, who then handed us off to our platoon Sergeant.

Sergeant Outlaw was our platoon sergeant. I had trouble processing this, my sleep deprived mind telling me I must have misheard his name. Who the hell had a last name of Outlaw? Outlaw stood around 5’ 8”, lean and taut like a wire, with an almost reptilian face that would later remind me of Miles Davis. He spoke in a leathery growl, and during those first weeks wore a cast on his left arm. I mention this because at one point, after a miserable performance doing pull-ups, he demonstrated how much of a sorry-assed pile of shit I was by doing twenty of them single armed, using the arm in the cast. His supporting Sergeant’s, Hicks and Felts, were tall, layered in muscle, and from all appearances, pissed to be alive. We were now part of Hotel Company Platoon 2085. We were the largest starting platoon in the company at that time, beginning with close to eighty recruits. We would graduate with forty-six recruits, the smallest platoon in the company.

We found ourselves under the explosive charge of all three drill instructors within seconds of Sergeant Outlaw taking over the platoon. They swarmed us, darting about as we stood in formation, screaming in our faces, their hot breath and spittle raking our cheeks. They overwhelmed our shell-shocked psyches with multiple orders barked in rapid succession, a drill instructor at each side of your face, screaming commands one after another, demanding to know why we were not following orders. We were commanded to GROW, and to respond with TALLER, straightening our spines while we screamed until our throats went raw. We scrambled about the barracks, recruits colliding with one another here and there as we swarmed in a mad and frenzied dash, ordered by screaming drill instructors to set up our racks and make our beds . We made them again after the drill instructors tore them apart, knocking over the bunks, and tearing off the blankets and sheets in a fit of rage. We could never move fast enough, never complete our tasks in the correct manner. While beds were being re-made, a number of recruits swept and mopped the barracks floor. Moments later the filthy mop water was dumped all over the floor by a disgusted drill instructor who couldn’t understand how we had managed to do such a lousy job and must think he was some kind of pushover to be fucked with. With hands on hips and shaking his head, he said he would show us that he was the wrong one to be fucked with. He ordered buckets of soil and rock fetched from outside and proceeded to toss it all over the barracks floor, mixing it in with the mop water. As drill instructors screamed in our faces we frantically tried to re-clean the floors and dispose of this muddy soup.

This was all in the first thirty minutes.

By the end of the first day we were bleary eyed and physically wasted. Our faces hung puffy with exhaustion, our eyes dazed and distant as if in shock while we stood as erect as possible for the end of evening roll call. Once in our racks and the lights extinguished muted whimpers escaped a handful of bereft recruits. Soon enough the whimpers were intermixed with a cacophony of snoring. I drifted off thinking to myself I had completed one day. One day out of ninety.

I was designated a diet recruit, otherwise known as a Nasty Fatbody. Red stripes were spray-painted on my gear to ensure everyone knew this. I had the pleasure of spending the first two months on restricted rations while I starved off the pounds. Every Monday morning all diet recruits would line-up prior to morning chow to be photographed and weighed. This was to ensure we were on track to hitting our ideal weight as designated by the Marine Corps height and weight standards. This also let the drill instructors know whether you needed some extra “classroom” time throughout the week to help excise those extra pounds. The diet was meager and bland. I considered it a chemical diet: with each meal a single piece of plain, dry bread, no cheese, no gravy, or condiments of any kind, as much fruit as you wanted, black coffee, vegetables, and single servings. I was plagued by constant hunger due to the amount of physical exercise we performed on a daily basis, though I began shedding pounds at an accelerated rate.

The first month was one long stretch of misery. Each day filled with exhaustive physical training, endless marching, deafening screaming, and physical punishment. Interspersed were classroom lessons in the Military Code of Justice, the proper rules of Marine Corps behavior, the ranking system and more. Class time was an endurance test marked by the somnolent wobble of the recruits’ heads as they fought to stay awake.

It was then the first recruit vomited, a convulsive gush that splashed to the floor. For a moment, all hung quiet and still. Sargent Outlaw shook his head in disgust and had begun to speak when another recruit vomited.

During the first few weeks of training recruits dropped like flies from our ranks. Some due to injuries, some to mental breaks, others that realized this was not for them and refused to do anything more. We were introduced to a variety of punishments and humiliations. Group punishment for the failures of single individuals was the norm. I believe this was to build a sense of group cohesion, and to persuade all platoon members to be at their best, and to work together. Unfortunately it didn’t have the intended impact. Our platoon was a mopey bunch of demoralized and unmotivated slackers who didn’t give a shit.

Pressure was applied. One notable day Sergeant Outlaw informed us we were not hydrated enough, obviously due to the number of recruits falling to injuries and other physical derailments. To combat this we were going to force hydrate. He explained this was simple. He held up a canteen and informed us to each fill our canteen and get back on the line in front of our racks. Once this was executed he told us we were going to fully drink the canteens and hold them over our heads to demonstrate they were empty by the time he finished counting down from ten. If anyone did not fully drink the contents of their canteen by that time we would do it again. The timing of this could not have been more unfortunate as we had just returned from lunch. Our standard military canteens held about a quart of water. That’s just a touch over 32 ounces, or about four glasses of liquid.

The first canteen stretched my stomach to an uncomfortable fullness. At the end of his count there were a few recruits standing in a puddle, their heads and shoulders dampened by the leftover contents of their canteens. On command we hustled into the bathroom, re-filled our canteens, and filed back on line. The second canteen left my insides feeling engorged, so much so it was painful to breathe. To our dismay, a few of those same recruits did not finish in time. Back on line with the third canteen, I looked at the water-logged and worried expressions of those recruits opposite of me.

It was then the first recruit vomited, a convulsive gush that splashed to the floor. For a moment, all hung quiet and still. Sargent Outlaw shook his head in disgust and had begun to speak when another recruit vomited. And then another. It was as if a rack of dominoes began to fall. Random recruits up and down the line jettisoned huge quantities of water and partially digested food onto the barracks floor. I felt a touch of nausea curdle in my throat, but was able to swallow it down.

There I was, another poor kid that needed an out and chose the military. It seemed to go against everything about my character, but that wasn’t uncommon in these barracks. As I walked the perimeter those evenings, I listened to the snoring of countless young men from broken homes, financially strapped families, from communities lacking in opportunity, options, and mentors.

Every few weeks a recruit pulled a few hours of guard duty. Woke from a dead sleep in the middle of the night, a recruit would fully clothe and walk about the barracks in an effort to stay awake while “guarding” the premises. The initial interruption to sleep was brutal, but once up and moving I didn’t mind it much. I would let my mind roam while walking the perimeter of the barracks, the snores of dozens of recruits undulating around me like some strange song of nighttime insects. I missed my friends and my girlfriend and would imagine being back home. I would think about how I had arrived there, all the possibilities and chances that amounted to that moment, alone in the dark in Marine Corps boot camp.

Since I was young my father had always mentioned the military as an option for any one of us boys. I had always rebelled against the hand of authority so I never entertained the idea. My parents also informed us boys that if we wanted to go to college, and they hoped we would, we were on our own financially. While my parents would never have used the word poor, we were a working class family that struggled to make ends meet. Paying bills was often a delicate balancing act of pressing needs marked by constant anxiety and stress.

There I was, another poor kid that needed an out and chose the military. It seemed to go against everything about my character, but that wasn’t uncommon in these barracks. As I walked the perimeter those evenings, I listened to the snoring of countless young men from broken homes, financially strapped families, from communities lacking in opportunity, options, and mentors. Young men who had burned bridges or were running from years of bad decisions, bad habits, and other dependencies.

Many words danced in my head during these late hours, lines of bad poetry and prose, words strung together in an effort to describe the harrowing experience of boot camp. During daylight hours I’d write snatches of these stanzas in the margins of my book of “knowledge”, or on small scraps of paper I’d hide within its pages.

I didn’t think much of this at the time. But the habit grew, and soon I was writing letters in bits and pieces over a series of days. In these letters I whined about the drudgery of boot camp, the monotony of seemingly endless days, these missives secreted away between pages detailing how to properly attend to a sucking chest wound and the codes of military conduct. It felt cathartic, a small release and a sense of homecoming, of touching a preserved space inside the drill instructors could not get at.

One afternoon I was chosen for guard duty while the platoon went out to run the “Confidence Course”. The “Confidence Course” is what you often see in movies depicting military training, a series of obstacles that need to be traversed that involves rope and wall climbing, mud, etc. This was a highlight of boot camp that I was disappointed to miss out on. Daytime guard duty amounted to being stationed at a podium near the barracks entrance. If someone came in, you bolted to attention, screamed out the personnel count on premise and then awaited whatever other questions might come your way. Standing at the podium, I pulled out my knowledge and pretended I was studying but instead began working on a letter. This letter contained a poorly worded poem describing death as being held in the barracks while having to sweep up a never ending tide of dust bunnies. This was some deep, introspective writing that was sure to captivate my girlfriend back home.

A captain walked into the barracks and made his way toward the drill instructors office while I scribbled these enthralling observations. Looking up from my work I saw his rank, knew that I was supposed to stand at attention and start screaming out the count on deck, and yet I did nothing. Without hesitation the captain was in my face, screaming about my dereliction of duty and lack of respect. To make matters worse, this brought the attention of the drill instructors, including the senior drill instructor, who had stayed behind. As I stood taking a barrage of insults my senior drill instructor knocked the podium out of the way, sending my knowledge spilling to the floor. My letter drifted out from the pages, a magnet for everyone’s attention.

My face reddened as the drill instructors read aloud my letter, laughing at the melodramatic word choices, feigning outrage at the words, “I hate the Marine Corps”. “Death by dust bunny? What the fuck does that even mean?”, Staff Sargent Brown bellowed. Sargent Felts was in my face to the point of his nose touching mine, promising he would ensure that I hated his beloved corps, that he would give me all the reasons in the world to hate every minute of it. This is also when they labeled me a pacifist. I don’t believe I was fully aware what a pacifist was at the time, but the designation may have been fitting. The situation left me filled with dread for the coming months, imagining a never-ending series of punishments and humiliations. And for a time this was true. When a series of recruits were getting bent in the classroom I’d often hear, “Recruit Jacobs, get your day-gone friggin’ ass up here!”, whereupon I’d get bent with the others even though I may not have committed any offense.

Second Phase Bootcamp

After the first four weeks of boot camp, we packed up our gear and headed north by bus to Camp Pendleton. It was here that we would complete our second phase training and conduct our rifle qualification at Edson Range. While second phase’s main focus was rifle qualification, it was also a time for field training and hiking, learning about heavy weaponry, handling and throwing grenades, navigating by map and compass, and more. It was during second phase that we hiked the Grim Reaper, a ten mile, full gear hike up the side of a mountain that was guaranteed to turn your feet into something approaching ground hamburger. It was also during second phase that I was no longer a diet recruit, a most welcome day indeed. I was allowed to enjoy some of the more “decadent” food items from the slop served up at the chow hall. After having felt starved for a month and a half I jumped at the opportunity to eat my fill.

Prior to second phase, and for reasons I can only equate to temporary insanity, I volunteered to be the artist recruit. This led to sleepless nights drawing and painting our second phase rifle flag. When rifle qualification day arrived each platoon marched onto Edson Range holding their flag high. The flag was supposed to be an embodiment of the platoons character and what I would equate to a house crest. Per the direction of Sergeant Outlaw our flag had the word “Epitome” emblazoned across the top in Gothic calligraphy. Below this I painted the menacing visage of a drill instructor peering out from the brim of his hat. Below this were silhouettes of a platoon marching across a mountainous landscape.

As Sergeant Outlaw explained to me, our platoon was to represent the epitome of the Marine Corps, an example and outcome of the highest standards. Our drill instructors were not our buddies. Our drill instructors didn’t celebrate our achievements like the other platoons, they did not praise us. We were held to a different standard, the highest standard, and for some reason this did not include positive reinforcement. It explained the hard nosed, no frills, all pain approach they used on our platoon.

“One shot, one kill” was a Marine Corps mantra, and winning the rifle qualification demonstrated our fitness in regard to this ideal. This was also an honor that I came close to blowing for our platoon.

Unfortunately, it didn’t work. We were far from the “Epitome” he so greatly desired. In reality we were demotivated at most times, feeling run down and overly harassed. When reflecting on this I’m inclined to feel that while this may have worked in years past it was not the right approach for my generation. Instead of motivating us to work together and to inspire us as a unit, it depressed and separated us. I would see this outcome again when in military school and when I was dropped into my battalion. There was something about my generation that didn’t respond to this type of coercion. Maybe because we were already jaded and knew this was a game we were all participating in, and at a point it amounted to unnecessary and tiresome harassment? No matter what it was, I understood it was the drill instructors job to prepare us for the possibility of life threatening, violent situations, situations of extreme psychological stress. I’m sure they gave zero fucks what we felt, or whether we desired positive reinforcement.

Sergeant Outlaw was proud of this flag and the praise it brought from the other platoons in our company. This led to more sleepless nights when he brought me a black and white portrait photo of himself and instructed me to draw it, twice, on sheets of white drawing board. Once complete he informed me these pieces would be joined together in a sleeve to hold documents. He told me he was going to keep it forever. I took this to be a compliment, and a slight smile may have touched the corner of my lips. He then told me to get the fuck out of his face.

Somehow our platoon took first place in the rifle qualification. This was a big honor, and of all the competitions with the other platoons, all of which we lost, this was the one that mattered most to our drill instructors. “One shot, one kill” was a Marine Corps mantra, and winning the rifle qualification demonstrated our fitness in regard to this ideal. This was also an honor that I came close to blowing for our platoon. To qualify one had to hit their targets a specified number of times in each of the different shooting positions (kneeling, laying, etc.), with points awarded dependent on where you landed your shots on the target. I qualified as marksman, the lowest rank for rifle qualification. I barely attained this, coming in one bullet hole shy of failing. “One shot, one fail” came to my mind after I learned how close I came to taking myself and my platoon down. I often wonder if that last qualifying round was found on my target with the assist of a drill instructor.

The days unfolded, each bringing new training, new experiences. We conducted biological warfare training, donning full hazmat suits and gas masks. We stumbled about, gas masks clouded over with condensation, swarming over the landscape like a demented hoard of zombies, recruits trailing off in every direction, suffocating in the unrelenting heat. Drill instructors cursed our incompetence while we flailed about, blind and disorientated, lost in the desert landscape. This culminated in learning how to don and clear a gas mask. We filed into a corrugated steel shed that served as a gas chamber. Once lined up along the perimeter of the shed, we were ordered to take off our masks and then to put them back on. This required you to draw a deep breath to force out the air in the mask so you could create a new protective seal from the outside air. The second you withdrew the mask your skin and eyes were set afire, and your nasal passage flooded with snot. When drawing a breath you began choking, your throat lined with a billion stinging needles, your lungs convulsing while you struggled for air. Released from the chamber, recruits pulled off their masks, some vomiting, most others trying to clear the long streams of snot that spilled from their nostrils and hung off their chins.

Field training required us to set up camp in the desert hills for a week. Each morning we awoke in the freezing dark of the Camp Pendleton hillsides to stand in our skivvies for morning count. Each morning , as we shivered uncontrollably in the cold, the platoon would mess up the count requiring us to do it multiple times. In the evening we stood naked with our canteen, canteen cup, and bars of soap, being instructed on proper field hygiene. We slathered our face, armpits, groin, and ass-crack in soap and then set about trying to properly rinse this off with a quart of icy water. Nevertheless, upon returning to our barracks at the end of field week two recruits had picked up field crabs. All of our gear and bedding were dragged outside while the barracks were scoured.

The weeks clipped by in rapid succession and toward the end of that second month we were stronger. We had adapted to the routines, and become impervious to the physical tortures of the classroom. We lost more recruits to injuries, but overall our platoon had weeded out those who were mentally incapable of handling the stress. At this point, so long as you stayed healthy, you were likely going to make it through. The end was in sight.

Third Phase Bootcamp

Right out of second phase and into third we embarked on mess hall and maintenance week. Because our platoon placed first for rifle qualification we were spared the drudgery of having to work the mess hall. Instead we were given various maintenance tasks throughout the depot. I found myself back at the receiving barracks, polishing brass and cleaning bathrooms, sweeping and mopping floors. It was an odd feeling to go from being micromanaged at all times to suddenly being left alone for days at a time. I’d wander the halls of the receiving barracks, polishing and re-polishing the same door handles and brass fittings, trying to look busy and distract myself from the slow ticking of the clock. I’d often disappear to the bathroom for long periods, sequestering myself in a stall to write letters to friends and family.

During second phase the drill instructors pulled back a bit on the amount of stress they normally applied. We surmised this was to allow us the focus we needed for rifle qualification, as well as keeping us from going postal now that we’d be handling live firearms. Coasting into third phase and maintenance week was another respite from the trials and tribulations we normally experienced. The majority of our days this week were away from the drill instructors. After reconvening at our barracks at the end of the day, there was a noticeable lightness to our conversations. There was joking and laughter among the recruits. I remember feeling that it wasn’t so bad.

It is hard to put into words the sounds, sights, and smells of forty-plus recruits simultaneously gagging, choking, and vomiting into toilet bowls and sink basins. It was almost otherworldly, bordering on a spiritual experience as it was so odd and mentally confounding, so beyond anything I’d ever imagined, witnessed, or participated in.

Then came the week after maintenance week. I believe this week is termed “Hell Week”. This was a sudden and abrupt shift back to the type of punishment, stress, and torture we’d experience during our first phase of boot camp. The highlight was a return to the water bottle torture we’d experienced previously, though now we knew when sent to refill our water bottles it was best to purge the contents of our stomachs. Our drill instructors had strategically waited until Italian food day at the chow hall, where we had filled our stomachs with heaping amounts of spaghetti noodles, sauce, and garlic bread.

It is hard to put into words the sounds, sights, and smells of forty-plus recruits simultaneously gagging, choking, and vomiting into toilet bowls and sink basins. It was almost otherworldly, bordering on a spiritual experience as it was so odd and mentally confounding, so beyond anything I’d ever imagined, witnessed, or participated in. After shoving a finger down my throat, I forcefully ejected the contents of my stomach into a sink with two other recruits, the sights and smells making the release easy. Our vomit splashed onto one another as it mixed in a chunky, blood red wave of partially digested noodles, stomach bile, and tomato sauce. The sinks were immediately clogged and overflowing as the other recruits did the same. Standing at attention after two rounds of this, our eyes red-rimmed and faces flushed, splashes of spaghetti-sauce vomit on the sleeves and lapels of our military fatigues, the drill instructors chose a handful of recruits to clean up this mess. The gods smiled on me as I was spared this unfortunate task, one that required the manual insertion of hand and arm into vomit filled sinks to extract the contents that plugged them.

The days were quickly moving toward the completion of Phase three. We trained and prepped for our final march qualification and final inspection. We lost both of these to the other platoons. Regardless, our spirits were up as we’d soon be seeing our families and loved ones.

And then it was over. Graduation day came. We marched into formation and when set at ease before the stands of family and friends awaiting us, having been set at-ease thousands of times by this point, I stepped in the wrong direction, moving right instead of left. To make it worse I corrected my position, likely calling undo attention to my blunder.

A short time later I found myself sitting in the smoking lounge of the airport with a Marlboro between my lips, staring out the window, trying to process how only hours before I had been a recruit and now was a Private in the United States Marine Corps. 12 weeks of training had passed. I had shed almost thirty pounds in the process. I felt proud for completing this challenge, a truly difficult physical and emotional endurance test.

Alongside this feeling of pride was a feeling of unease. I was a Marine, a designation I had earned through hard work and fortitude, and yet inside I felt like an impostor. I felt like someone playing a part, feigning the Esprit de Corps so championed throughout the previous weeks and weeks to come. I was overwhelmed by this sense of not fitting, of not belonging. It was like the final move during our graduation formation, when set at ease only hours before. I was right there, in the mix, and then I stood out, odd and perplexing.

I would venture home for a week, feeling the same in some ways, feeling profoundly changed in others. Meeting my girlfriend and S_ at the airport, I was filled with happiness while also feeling estranged from them. It had only been three months but the distance that separated us now felt immense. We piled my duffle bag into my girlfriend’s car, and made our way back to the south suburbs of Chicago. Sitting in the back seat was a 40oz of cheap beer and a boom box I had requested. In the tape deck was Sepultura’s album “Chaos A.D.”. Soon the car was filled with the thundering drive of “Refuse/Resist”, a song in complete opposition to the rigid conformism and destructive might of the military.

It would be a short respite before shipping off for Marine Combat Training and then Military Occupational Specialty training. It would be months before I was home again and this filled me with sadness. There was an odd feeling of having accomplished the task, of being done, that I should be able to continue on with my life. It was nonsensical, and the reality that I had four years ahead of me stood in weighty opposition to this sensation.

It’s difficult to re-visit this time and capture my experience of Marine Corps boot camp without detailing every punishment, every challenge, every laughable moment. So much happened and it would be exhaustive to detail it all. So much of this experience still churns inside, little movies of time and place, some bubbling to the surface while others fade into lower mental depths. I’ve tried to capture those that are, for one reason or another, more at the forefront of my memories. Peering at photographs of the recruits I graduated with, I’m left wondering where these people are today? I’m left with an emptiness when I consider that we probably shared one of the most significant experiences of our lifetimes and yet outside of one recruit, I never saw any of them again.